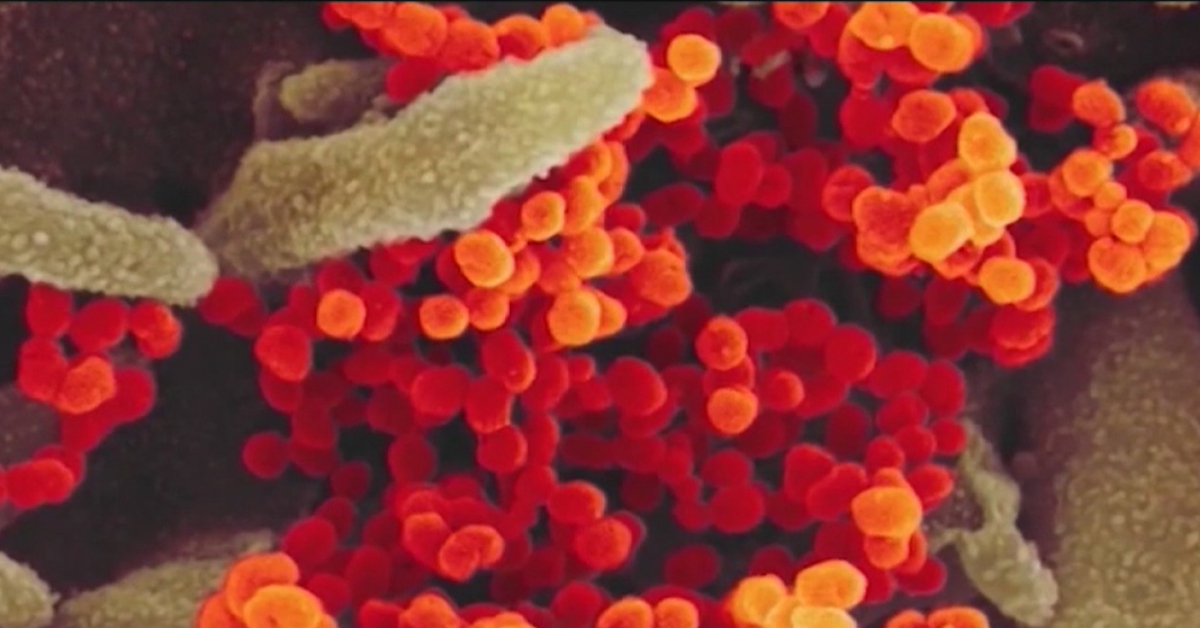

Infectious disease threats, epidemics and pandemics are inevitable in this modern world where international travel dissolves borders. In the past decade, we have witnessed this first hand. From avian influenza to Ebola virus disease, Zika virus disease and, of course, the current novel coronavirus (COVID-19) disease emergency originating in China.

Preparedness is key to responding to biosecurity threats. This is especially important for new or emerging diseases where prevention and treatment options may be lacking. While infection control measures such as isolation of confirmed cases, case control of symptoms and bans on international travel are vital, a robust national infrastructure and innovation pipeline to support the development of vaccines, drugs and therapies is also crucial.

Infrastructure and facilities need to be appropriately funded to be ready to respond to often unpredictable disease threats in a minimal timeframe. This includes funding and maintaining unique libraries of chemical compounds that could hold a new drug for the next infectious disease pandemic, banks of cells (human, bacterial, viral, parasitic and animal) ready for testing as disease models, and pre-clinical and clinical facilities to test the suitability of new drugs, vaccines and therapies.

This need is all underpinned by Australia’s real asset – our talented and skilled workforce. If we don’t prioritise the support of our highly skilled facility managers, technical experts and experienced and up-and-coming researchers, we just won’t have the technical and intellectual capacity to respond to the disease threats that will be inevitably thrown at us in the future.

In Australia, facilities funded under the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS) underpin our biosecurity response strategy, including the funding of a skilled workforce of more than 1900 people. NCRIS funded facilities have contributed to collaborative discoveries like the world’s first Hendra virus vaccine, the finding that bats are the likely natural host for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and current research on the development of a vaccine for COVID-19.

Sharing of data is also critically important in an infectious disease emergency, epidemic or pandemic scenario. The potential benefits to human health that can be made when academic and industry barriers to collaboration are removed cannot be underestimated. In the case of the current coronavirus emergency, China made the genetic sequence of the COVID-19 virus publically available, facilitating global research and collaboration.

What has consistently emerged from the current COVID-19 emergency and other recent infectious disease threats is that the investment made by Australia in biomedical infrastructure, data sharing and biosecurity preparedness is paying off in our ability to respond, collaborate and innovate. Investment in key facilities and, equally importantly, in continued support of highly skilled facility managers, project managers, technical experts and researchers must continue to be a high priority and have bipartisan support from Federal and State government. Industry and philanthropy also have important roles to play in innovation and preparedness, in particular for funding or co-funding research projects and equipment to leverage major government investments.

The threats posed by known and new infectious diseases are likely to continue, or even increase due to international travel and changes to our environments. We cannot completely predict or avoid infectious disease outbreaks. What we can do is make sure we are prepared to tackle these events with a robust innovation infrastructure supported by highly trained people who can get things done.

Professor Katherine Andrews is an infectious diseases research leader and Director of the Griffith Institute for Drug Discovery at Griffith University.