As we come toward the end of another summer of climate extremes its time to ask ‘if not now, then when is it a convenient time to talk about climate change’?

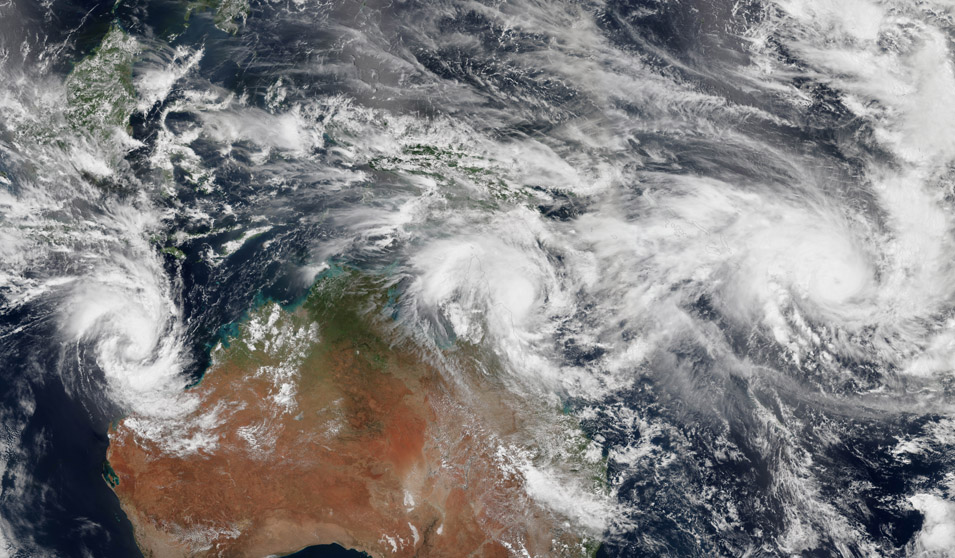

IMAGE: FLICKR, 350.ORG

When tragedies such as Cyclone Pam strike the primary focus is on survival and rebuilding and it seems rather impertinent to talk about climate change. But history proves disasters are precisely the time to talk about preparing and adapting to extreme events – and climate change is the greatest potential disaster ahead.

Is climate change to blame for extreme weather?

It’s almost impossible to attribute a single disaster event to climate change, mostly because when we talk about climate change we talk about averages. Extreme events such as bushfires, heatwaves and floods occur infrequently, making up the “tail ends” of a frequency distribution graph (see below), and as many argue, extreme weather events are all part of life in Australia. But the high intensity cyclones of recent years, including Cyclone Pam, give climate scientists a chance to look at the conditions that create ‘monster’ storms and marry them up with climate predictions. The Climate Council released a briefing on Cyclone Pam and connected the above average sea surface temperatures with the increased energy and intensity of the storm. Add to that storm surge combined with higher sea levels and increased flooding and inundation were experienced. It was a step further than many science commentators tend to be willing to go with the science of climate based on averages and probabilities. But the message came not only from scientists but also from the Vanuatu Government.

In many ways it actually doesn’t matter if we demonstrate climate change is responsible for extreme events, because we still have much to adapt to, particularly in Australia, with our current naturally variable and sometimes dangerous climate. For developing countries their vulnerability is even more pronounced and makes the issue even more urgent.

While Australians are well aware of the risks of the bushfire season, cyclone season and storm season, the truth is we still face loss and tragedy with each and every event – loss of life, loss of property, loss of business, loss of lifestyle. And while Australians have a great spirit of mateship and sense of sympathy for victims of disasters, we all shoulder an enormous burden from disasters.

So I would argue there are at least three very good reasons we should be talking about adaptation (at the very least) and planning for increasing climate change impacts when disasters like the recent high intensity cyclones hit. They are drawn from consideration of a number of historical extreme events and the adaptation actions that came out of them.

Emotion drives change

First, are the emotive drivers of policy change. There is always going to be “politicising” of disasters and tragedies (such as the asylum seeker debate). The idea that someone’s suffering or loss can, if nothing else, prompt change that might prevent another from a similar loss is tragically a common pathway for policy or legislative change.

Consider eponymous laws in Australia such as Queensland’s “Jet’s Law” following the death of a baby in a car accident. We have recently considered many historical extreme events, and seen that in many cases it is the pure horror and unacceptability of a disaster that drives policy change.

If we don’t act when the greatest public horror and desire never to experience the same scale of loss is so keen in our minds (and at the forefront of the media reporting cycle) then we will never bring about changes needed to address infrequent but disastrous events. The risk with increasing disasters, and continuing extreme summers is that it will become the new norm and the loss will be accepted as a normal part of life.

Economic cost

Second, is the economic burden (not to mention emotional and physical stress) that is placed on Australia.

Consider the summer of 2010-2011 – an exceptionally disastrous summer for Australia. In that summer alone, Australia faced the potential of a major locust infestation, bushfires in the Perth Hills, heatwaves in Sydney, major flooding in Queensland and Victoria and the crossing of Tropical Cyclone Yasi in north Queensland.

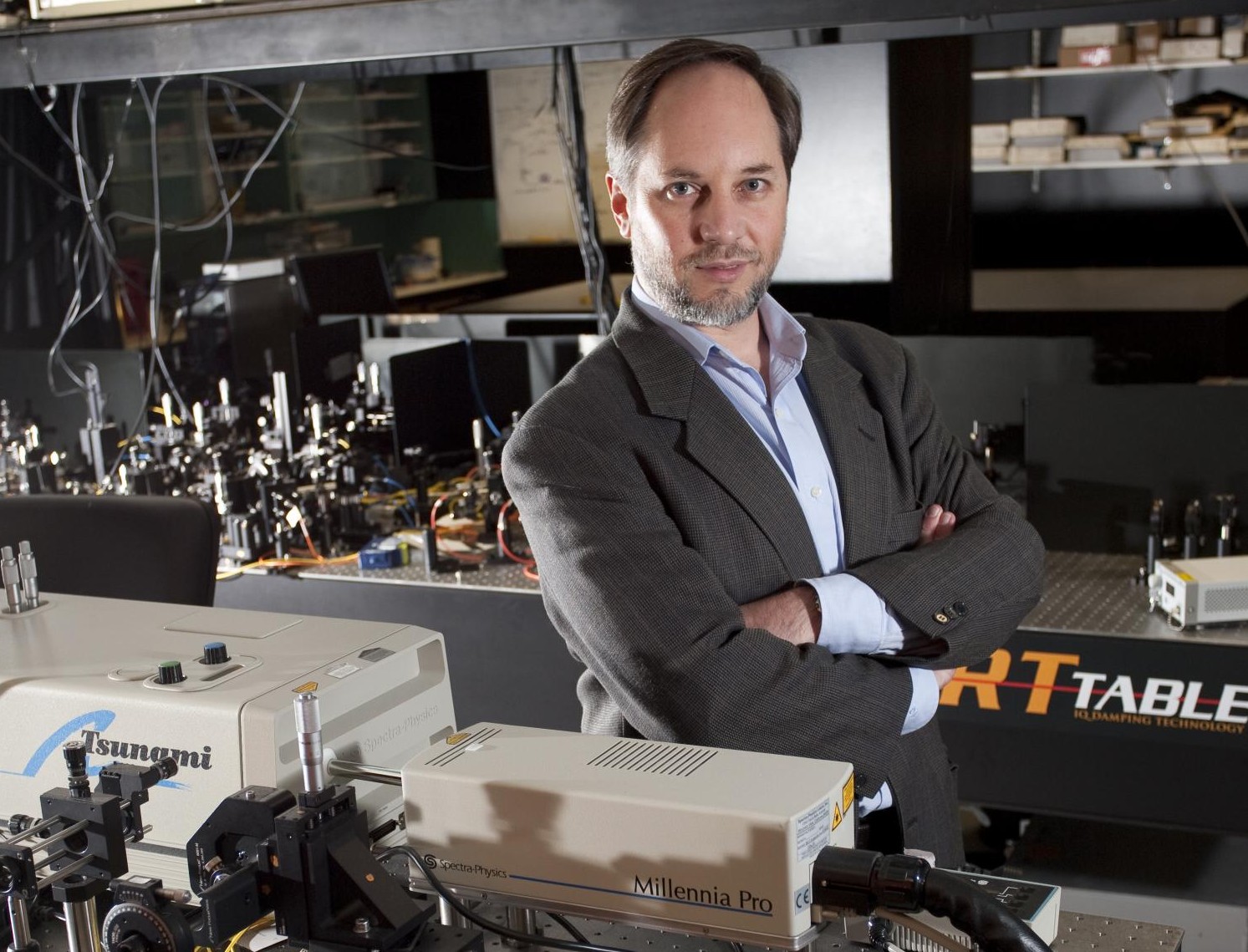

Professor David Karoly at University of Melbourne and I totalled the reported cost of these events and came up with A$12 billion in government expenditure and almost A$4.5 billion in insurance claims – a staggering A$16.5 billion in cost.

While the personal toll for people living in affected areas is unimaginable, and in many cases still ongoing, a simple division by the number of Australian households (8.18 million in 2011) suggests that the cost to every household was in the order of $2000 – for one summer. Since then there have been more fires, more cyclones, more floods and in some parts a seemingly never-ending drought.

Acknowledging that not all of this comes out of our hip-pockets, the indirect costs through taxes, insurance premiums and the costs of goods and services are likely to be significant.

It’s a cost that is going to be recurrent and good science and logic tells us that we should be expecting this to be a regular and increasing cost. But there is equally good evidence and logic that tells us that by planning and adapting now we can reduce that cost burden. The productivity commission has completed an analysis of the Australian government’s funding model for responding to disasters. The commission was clear – the number and cost of extreme events has increased in the last two decades and the government overspends on disaster recovery and underspends on preventative measures that would reduce the impacts of natural hazards. In their investigation, the Commission noted “Groundhog Day anecdotes abound”. That the same bridge might be rebuilt year after year due to flooding is an unsustainable failure of policy and funding that the government recognises must be addressed and soon. The Productivity Commission’s inquiry makes it clear that the Australian government recognises that the current model is not sustainable, that more must be invested in building resilience and the government can no longer be the insurer of last resort.

Battling the Aussie battler

The third is to ensure that “stoicism” is not mistaken for building resilience. Through a review of natural disaster case studies from across the world, it was almost universally consistent that many victims of those tragedies were under prepared for extreme events, even those consistent with existing climate patterns.

In many cases however, it was the actions after the event that were most significant in building communities that were prepared for future events – adaptation to an existing or potential risk.

Rather than shrugging our shoulders and accepting extreme events as part of life in Australia it’s time to consider if we can do better. There is already some movement in this direction. For example in Queensland, the government planned to include “build-back better” reconstruction following the floods and cyclones of 2010-11.

Following disaster, the urge to return to normal as quickly as possible is completely understandable, but we need to take the opportunity to address some tough questions about what risk and cost we are willing to accept and be prepared to make change.

Discussions should include deciding where it is reasonable for houses to be built, housing construction standards and emergency responses. The conversation needs to include a serious and significant commitment to financial and social investment now to reduce future risks. This would amount to genuinely building resilience.

Agenda 21, Global Governance is the aim. Climate Change is the key to achieve it. Wake up to yourself.