How much information can a single grain of sand give you? According to the Australian Rivers Institute’s Professor Jon Olley quite a bit: from the origins of Australia’s cultural history to the environmental problems of today.

This article was first published in Impact @ Griffith Sciences magazine. Click here for more details

“One of my PhD students discovered that human nostril hair was the best way to move around the grains of sand, bet you wanted to know that!” Although this factoid may not prove useful to many, the plight of single grains of sand and the stories they can tell occupy much of Professor Jon Olley’s time.

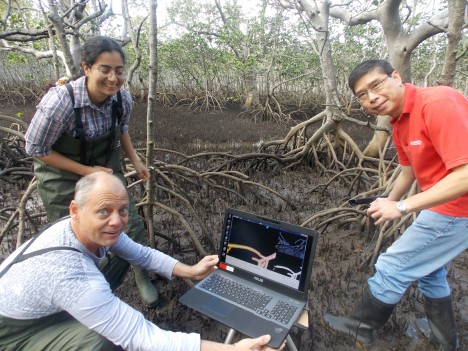

Jon describes himself as a professor of water science but his research is offering insight into a variety of issues that stray far from this title, from how land use is impacting on delicate sea-grass beds to tracing the origins of Indigenous culture in Australia.

This array of research is focused on a technique that Jon first started working on almost thirty years ago through his PhD with the University of New South Wales, supported by CSIRO, on the application of radio nuclides to tracing sediment movement through large river systems.

With improvements in equipment and analysis Jon can now use a single grain of sand to tell some very interesting stories.

As Jon explains, “Every single grain of sand, a crystal of quartz, acts as a clock, it can store energy. When you expose the grain to sunlight it releases that energy, setting the clock to zero.”

“When the grain is buried underground in a soil or sediment profile it builds up an energy charge in the crystal. If we bring the grain of sand, in the dark, back to the lab we can measure that charge giving an indication of how long since the grain of sand saw sunlight.”

“We have to load up individual grains of sand, under red light onto a very small grid network (this is where the nostril hairs come in).We can then expose them to a radiation source and assess the energy given back by the quartz crystal to give a the dating estimate.”

The accuracy of the technique is about 10 per cent and can go back around 300 000 years.

Jon has used this dating process to answer questions in numerous fields of science. One field that triggers Jon’s interest is working with Indigenous communities to build a full profile of Australia’s cultural heritage, using the technique to date ancient ceremonial burial and cremation sites.

Jon adds, “Few Australians would realise we have some of the richest cultural heritage of anywhere in the world. At Lake Mungo, Mungo man was discovered in 1969 and is one the oldest ritual burial site in the world. The body was rubbed with ochre before being put in the ground.”

“I’m keen to look at the geology of the land around there. There could be many more burial sites yet to be discovered that could pre-date Mungo Man. If you look up the Darling River there are numerous other lakes that are very similar to Lake Mungo.”