Liberal Democrat Senator David Leyonhjelm recently said Australia should not recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as the First Australians in legislation because the evidence was only “conjecture”.

He raised his concern when he spoke in the Senate to oppose the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (Sunset Extension) Bill 2015, part of which aims to recognise that Australia was first occupied by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. He said:

This is conjecture. Archaeologists make extraordinary discoveries all the time, and one of those discoveries could be that someone made it to Australia before the Aborigines.

For him, the idea that archaeologists may one day show that Aboriginal people were not the “first Australians”, is one reason why legislation is an inappropriate place to record Indigenous or scientific views.

Statements like this belong in scholarly research not legislation. Ever since the Enlightenment we have accepted that questions of fact are resolved by evidence not by decree. You cannot legislate a fact.

He also feels that recognition singles out a single ethnic group.

Setting the question of legislating fact to one side, it’s worth looking at Senator Leyonhjelm’s question of who were the “first Australians” and what evidence exists to suggest they were the ancestors of modern day Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Not the first to question the First Australians

In making his first point, the Senator may be echoing earlier claims for a pre-Aboriginal population of Australia. But such views are as much out of step with present-day archaeology and human biology as they are with Indigenous tradition.

Writing in the magazine Quadrant, the historian Keith Windschuttle claimed that Indigenous Australians should not have Native Title rights because they were not the first to occupy Australia.

He claimed that over most of the continent they had wiped out an earlier group, the sole survivors being represented by pygmies of northern Queensland.

He employed an outdated theory known as the trihybrid model for Aboriginal origins, developed initially in the 1930s, to support his claims. He wrote:

[…] the fact that the Australian pygmies have been so thoroughly expunged from public memory suggests an indecent concurrence between scholarly and political interests.

In addition to this hint of conspiracy theory, there was at least one major problem with his argument: there is no evidence that pygmies ever lived in Australia.

In a similar vein, the famous distinctive Gwion Gwion (Bradshaw) rock art in the Kimberley region of Western Australia has been used to support claims that there was a pre-Aboriginal population in Australia.

Again, there is no evidence to show that these magnificent galleries, numbering in their hundreds, were produced by anyone other than the Aboriginal people of the Kimberley.

An extensive record for the First Australians

In addition to Indigenous peoples’ own understandings of their origins, archaeologists, anthropologists and other scientists have since the 1950s accumulated an enormous body of evidence relating to the First Australians.

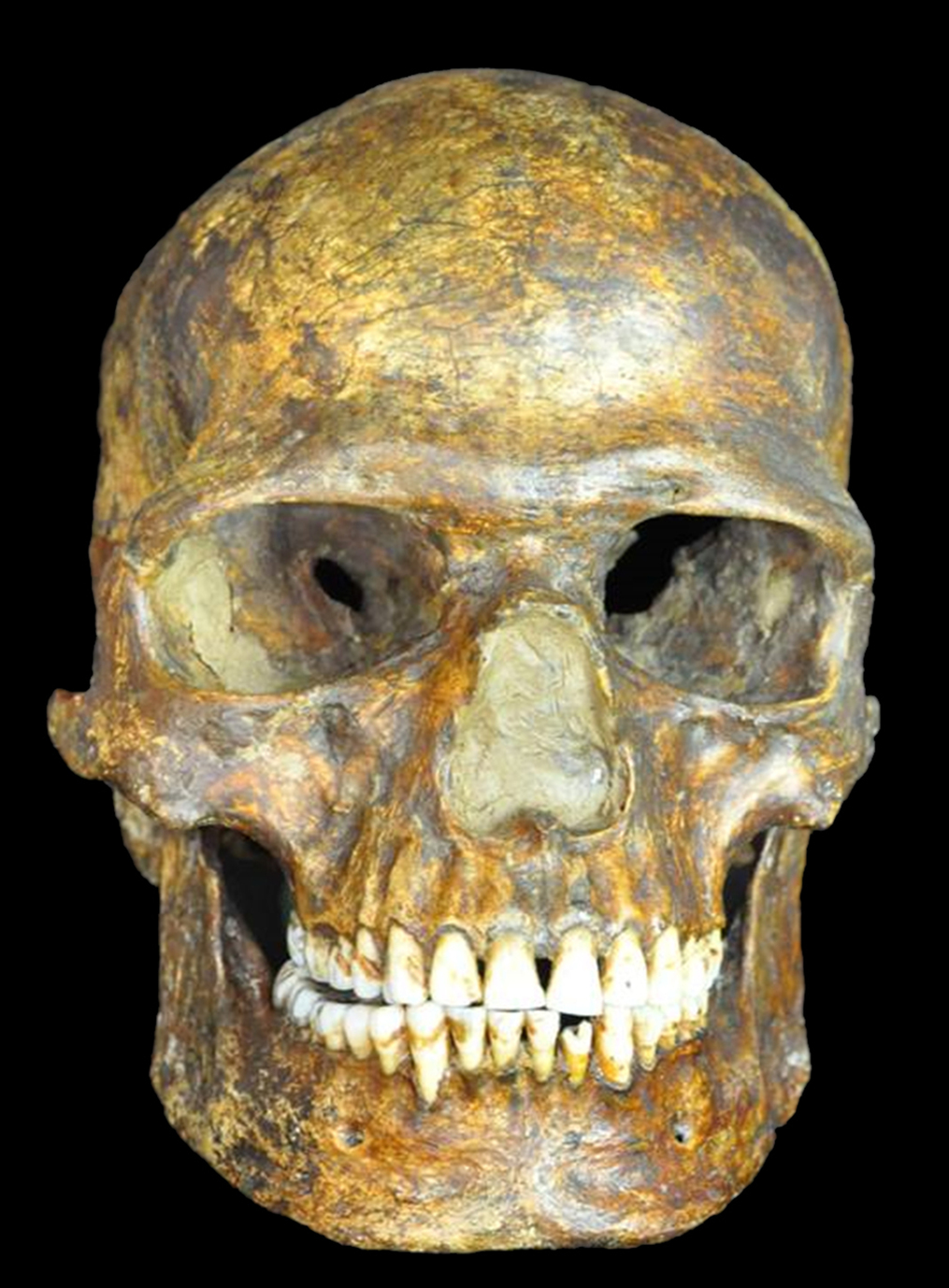

Australia’s population history is complex, but from the fossil human record, which includes the very early burials of Mungo Man and Woman some 42,000 years ago, it is clear that there are strong physical similarities between these earliest human remains and modern day Aboriginal Australians.

This is further supported by the record from Aboriginal genomes. Studies in genetics explore the relationships between ancient populations by looking for variations in DNA that reflect genetic history. This can tell us things such as how long ago one group may have diverged from another.

Genetic studies can be done in many different ways, by studying the DNA of populations today or recovering ancient genomes. There are different types of DNA that can be studied too, those from mitochondrial DNA, or those from nuclear DNA.

Geneticists search for unique genetic signatures in populations that reveal clues to patterns in ancient relationships and movements of people (migrations).

The first Aboriginal full-genome study in 2011 showed an unbroken Aboriginal lineage over 2500 generations, or about 60-75,000 years, the longest continuous lineage outside Africa. It identified a number of genetic signatures that were unique to Australia.

Over the millennia, some visitors to the continent may have intermarried with the First Australians, but they would have been small in number and are likely to have had very minimal impact on the Australian genotype.

Some of the most important genetic work demonstrating a very ancient Aboriginal ancestry has been through the long term study of Aboriginal mitochondrial DNA by the Sydney based researcher Sheila van Holst Pellekaan. Her research indicates that, relative to the colonisation of extreme regions of human migration such as America, Australia was inhabited very early.

We are now able to reliably compare genomes of modern populations to ancient Aboriginal remains, due largely to the dramatic improvements in the last few years in ancient DNA recovery. Different peoples may have come to Australia at various times, but the record shows quite clearly that there is no evidence for population replacement.

Hidden history

There has been reform in education, with the national syllabus bringing the archaeological record – until now locked away in academic journals and museum collections – into the classroom.

Archaeological landscapes, like the extraordinary Willandra Lakes World Heritage Areaor the remarkable galleries of the Quinkan rockshelters in Cape York (the inspiration for the children’s book by Percy Trezise and Dick Roughsy), recount powerful Australian histories.

In a similar way the recent First Footprints ABC television series publicised Aboriginal histories from around the continent. Stories of European exploration, settlement and the ANZAC spirit are important, but spanning only half of one per cent of human history on this continent, they are the tip of the iceberg.

Senator Leyonhjelm’s speech was important. We hope it provokes a conversation about what makes the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples the first in this land. But his objections seemed to overlook another point.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be recognised in the constitution not just because they go back to the beginning of human occupation. They should be recognised because this land was theirs before it became Australia the nation. That’s something we should all be able to appreciate.![]()

AUTHORS

Michael Westaway

Senior Research Fellow, Environmental Futures Research Institute at Griffith University

Joe Dortch

Honorary Research Fellow at University of Western Australia

Comments are closed.