As the Bureau of Meteorology has already warned us, Australia is in for a hot, dry summer as the current El Niño takes hold. Those conditions are ideal for blue-green algae to bloom in lakes, ponds and reservoirs.

Photosynthesising bacteria, also known as cyanobacteria, are found in all aquatic environments from the tropics to the poles. Most species have no adverse impact on the environment, but a few have nastier effects, and some are toxic to humans and animals.

Blue-green algae can form vast “blooms”, some large enough to be seen from space. In the Australian drought summers of 2009 and 2010, for example, hundreds of kilometres of the Murray River suffered major cyanobacterial blooms, which hampered the use of water for drinking, agriculture and recreation.

These blooms occur mostly in still water bodies and can be found throughout Australia. Some blue-green algae form visible surface scums, while others remain hidden in the water column. Some live in freshwater; others float in the open ocean or even live on the sea bed.

Tiny and toxic

The toxins produced by some blue-green algae can affect the nervous system, the liver and kidneys, or be toxic to cells more generally. Humans can be affected by drinking contaminated water or eating affected shellfish. Direct contact with water can also cause itching and rashes. Worse still, the toxins can remain in the water even after the blue-green algae themselves have vanished – in some cases for weeks, depending on the conditions.

Larger blooms tend to occur where there is an excess of nutrients, often the result of fertiliser runoff from intensive agriculture or other degradation of the catchment system. This means that, throughout Australia, the potential for blooms is increasing.

Water temperature also influences algal blooms, for two reasons. First, blue-green algae grow faster in warmer water and, second, warmer temperatures increase “thermal stratification”, in which a warmer surface layer overlies deeper, cooler water. Stratification allows cyanobacteria to flourish in the warmer sunlit surface waters because of their unique ability to make themselves float.

So how do you steer clear of blue-green algae? The obvious tips are to avoid drinking untreated water from still, calm water bodies, and to be mindful of children or dogs playing by the water.

Green surface scum is the most obvious tell-tale sign of an algal bloom, but not all species of cyanobacteria form scums. Discolouration of the water, particularly a green colour, can also indicate the presence of blue-green algae. Some species, such as Microcystis, give off a distinctive odour, although some other blue-green algae also create musty-smelling chemicals that are non-toxic.

It is comforting to know that if water quality is at risk, your local water authority is probably on top of it already, and will typically erect warning signs each summer. Many lakes and reservoirs are routinely closed for recreational use to protect the public from toxic blooms during the hotter months.

Blooming hot

The forecast hot, dry summer is likely to be a boon for blooms, given that blue-green algae prefer warm, still water. This means that areas that typically get algal blooms might find they are bigger and longer-lasting this summer. In Australia’s southern states, the blooms might also start earlier in the summer and last longer into autumn.

But the scale of blooms also depends on nutrients, so reducing the amount of nutrients that are washed off the land during rainfall events can provide a way of controlling them. This can be done by reducing land degradation, for example, reducing erosion, creating vegetation buffer zones along river banks, and avoiding excessive fertiliser use.

Some of these processes will take time to implement and therefore won’t help us this summer. But combating cyanobacteria in the longer term will help to protect the environment, allow continued recreational use of water and, most importantly, protect our precious drinking water. ![]()

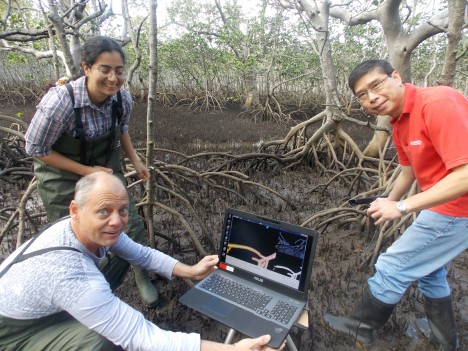

Know More: Australian Rivers Institute

Authors

![]() Anusuya Willis

Anusuya Willis

Research Fellow, Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith University

![]() Professor Michele Burford

Professor Michele Burford

Professor of Aquatic Ecology, Griffith University

“…the potential for blooms is increasing…”

Rubbish.

One hundred and ten years ago Enoggera reservoir, which is located near Brisbane, had algae problems. The report covering it also made mention of algae being a problem world wide in water catchments. So there ain’t nothing new here.

http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/97516480?searchTerm=%22toxic%20algae%22&searchLimits=dateFrom=1800-01-01|||dateTo=1939-01-01

I hope not to many of my taxpayer dollars were wasted on this so-called research.

Woomera, there is evidence of algal blooms in Shakespearean times too. And of course life on this planet started as a large algal soup. So yes, there have always been algal blooms. And no, it’s not a new problem.

But I think the point that’s being made is that the intensity, frequency, duration and distribution of noxious algal blooms has increased dramatically in recent decades. That’s recorded fact. So where blooms were once isolated to certain waterways under specific conditions they’re now more widespread, longer lasting and heavier – and they’re shifting the natural balance.

A couple of decades ago an algal bloom in a local waterway was newsworthy. Now it’s normal.

Once a waterway becomes characterised by frequent, intense algal blooms it starts to affect the other aquatic communities, particularly higher vegetation. This in turn favors more algal blooms, creating a permanent shift that’s hard to reverse. And with that change comes shifts in aquatic fauna too.

Notice also that the 1904 news report talks only about “remedying” the problem with engineering and chemical treatments …. something that has continually failed to be effective over the past century in the vast majority of affected waterways (usually at massive expense to taxpayers). It’s much like taking an asprin to fix a headache when drinking a glass of water could have prevented it in the first place. Drs Willis and Burford are addressing the cause of the algal problem, which is to be commended.

As a scientist, fisherman, recreational waterway user and father, I’m very happy to think that some of my hard earned taxpayer dollars might be invested in understanding our waterways. By far the majority of my tax dollars are spent on hair brained government initiatives that should never see the light of day. At least a small proportion is being used for something worthwhile.